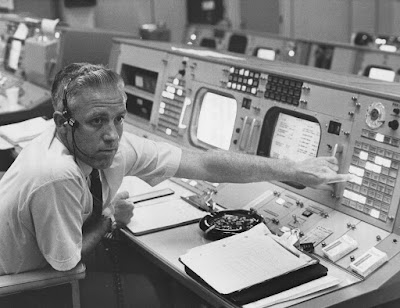

Aboard Gemini 8 were two first-time astronauts who would go on to legendary careers, Neil Armstrong and David Scott. At the Mission Control Center in Houston, that mission marked the first time that someone other than Chris Kraft was lead flight director. A soft-spoken Englishman named John Hodge was on console.

Six hours and four orbits after Gemini's launch, Gemini 8 and the Agena became the first spacecraft to dock in space, reaching an important milestone for the upcoming Apollo missions to the Moon. But a half hour later, the docked spacecraft banked without explanation and then began to spin nearly out of control while out of contact with the Earth.

When communications were re-established, Armstrong reported: “We’ve got serious problems here. We’re tumbling end over end up here. We’re disengaged from the Agena.”

Flight Director Hodge tried to make out the garbled transmission from Gemini. “Did he say he could not turn the Agena off?”

“No, he says he has separated from the Agena and he’s in a roll and he can’t stop it,” CAPCOM Jim Fucci replied.

Hodge was faced with the first life-and-death emergency situation in the U.S. space program. It was quickly established that the dangerous spin was caused by a stuck thruster on Gemini, not the Agena. But because Armstrong used re-entry thrusters to bring Gemini under control, the mission rules said Gemini had to return to Earth as soon as possible.

Hodge ordered Gemini 8 back home, and so Armstrong and Scott splashed down safely in the western Pacific Ocean after less than 11 hours in space rather than three days later in the Atlantic as planned.

The dramatic events of that day were the climax of Hodge’s career as a flight director, but he went on to prepare Apollo for the lunar landings that followed the first landing on Apollo 11, and he later played a key role in the early days of the program that led to the International Space Station. Hodge passed away on May 19, 2021, at his home in Virginia at age 92.

At the time of Gemini 8, John Dennis Hodge, then 37, stood out from most NASA flight controllers with his English accent, his graying hair, his pipe and his tweed jackets. Born in Leigh-on-Sea, England, on February 10, 1929, grew up in London and he studied aeronautical engineering at the Northampton Engineering College, now City, University of London, graduating in 1949. His original plan to study biochemistry had been frustrated when veterans of World War II got first choices for university positions.

He went to Vickers-Armstrong for a 12-month apprenticeship, followed by another two years in the aerodynamics department. His interest was in supersonic flight, but the British government, nearly bankrupted by the war, was cutting back.

His new wife, the former Audrey Cox, wanted to travel before settling down, and opportunity beckoned at just outside of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, where Avro Canada, an offshoot of the Britain’s Hawker Siddeley Group, was about to start work on a Mach 2 supersonic jet interceptor known as the CF-105 Avro Arrow.

So Hodge began work in 1952 at Avro Canada, where almost from the beginning he worked on the Arrow. “I did the [jet engine] intake and the ram, all the inlets. Then they needed a guy to take over the airloads group. I was put in that job.” Later on he moved to flight testing on the Arrow.

The soaring cost of the Arrow program had always concerned the Canadian government, and on the day in 1957 the first Arrow was rolled out of the hangar, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, sending an unequivocal signal that nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles were becoming the major threat to North America in place of the bombers that the Arrow were designed to defend against.

The Canadian government abruptly cancelled the Arrow program on February 20, 1959, throwing 2,000 engineers and thousands of others out of work. This was just months after the National Aeronautics and Space Administration had been established in the United States and charged with launching humans into space in Project Mercury.

“Most Americans thought that Mercury was going to be a fly-by-night reaction to Sputnik that wouldn’t last that long,” Hodge said. “That was the general expectation. Most serious engineers in the States weren’t the least bit interested in the Mercury program. So that left it wide open for the younger people.”

In March, leading officials from NASA flew to Toronto and hired 25 British and Canadian engineers from Avro Canada to work on Mercury as part of the Space Task Group in Hampton, Virginia. Another six were hired soon after, and in 1961 NASA announced that STG would move to Houston, Texas, in the Manned Spacecraft Center that a decade later was renamed the Johnson Space Center.

Hodge was hired for his variety of experience, especially in flight test, and was one of the most senior members of the group from Avro. Because of the urgency of NASA’s mandate, the immigration procedures for the new hires were completed in record time, and the Avro engineers reported for work at STG in April, 1959.

Assigned as the assistant to Chuck Mathews, the head of the operations division, Hodge quickly became involved in drawing up the mission rules for Mercury. These rules would, among other things, cover decisions on whether to continue a mission or abort it when a problem cropped up. Along with others from Avro, Hodge was heavily involved in setting up Mercury’s round the world tracking network.

As Mercury geared up in 1961 and 1962, he became Kraft’s deputy as chief of the flight control division. For the first three Mercury orbital flights in 1962, Hodge was assigned to the tracking station in Bermuda, ready to take over as flight director if the Mercury Control Center at Cape Canaveral experienced a serious problem. Moments before John Glenn was launched on his historic orbital flight on February 20. 1962, Hodge had to call a short hold in the countdown while he dealt with a problem with the computer in Bermuda.

The final Mercury mission was Gordon Cooper’s Faith 7 flight in May 1963 that was due to last 34 hours. NASA decided to implement 12-hour shifts with two teams of flight controllers. Chris Kraft, who had been flight director for every previous Mercury flight, became flight director on the day shift and Hodge was designated flight director on the night shift. Hodge became the only person other than Kraft to take the reins of Mercury control.

“I can’t remember anything spectacular during that period,” Hodge said of his first shift as flight director. “Most of the time I was on, we were planning for the next phase and [Cooper] was asleep. Our job was really a planning function. Which is a job I sort of took over in later missions, when we started going to Gemini and Apollo. My reputation was for planning for future events, which was a job I liked doing anyway.” One lesson learned during this flight was that two shifts of flight controllers probably wouldn’t be enough for longer duration flights, so flights in Gemini and afterward had three daily shifts of flight directors.

Early in 1965, the Gemini program began in earnest with the new Mission Contol Center in Houston nearing completion. The robotic Gemini 2 mission, and the first crewed Gemini flight, the three-orbit Gemini 3, were controlled from the Mercury Control Center at the Cape under Kraft, while Hodge served as flight director in the backup center at Houston.

The four-day mission of Gemini 4 in June 1965 was the first flight to be controlled from the new control center in Houston, and the first to be controlled using three shifts of flight controllers, rotating each day. In April, NASA announced four flight directors for the upcoming Gemini missions in 1965: Kraft as mission director and flight director on the first shift, The second shift worked under a 31-year-old newcomer to the ranks of flight directors, Eugene Kranz. Hodge was put in charge of the third shift, also known as the planning shift. Glynn Lunney was named as backup flight director.

Each flight director took a colour that would be used to designate their team. Hodge chose blue, making him blue flight, in charge of the blue team. Kraft chose red, Kranz white, and Lunney black under a tradition that long endured.

By the time of Gemini, Hodge was head of the MSC’s flight control division, supervising a large group of engineers. He had the responsibility of building up the group of flight controllers for Gemini and Apollo, and so he was hiring people “left, right and center.” Between flights, his flight controllers were busy planning missions; drawing up documentation, flight plans and mission rules; and closely reviewing results from previous flights. As well, they worked on simulations of flights, mainly possible flight emergencies, with the astronauts in spacecraft simulators hooked up to the flight control rooms.

The flight control setup continued through the missions of Geminis 5, 6 and 7. Hodge was involved in helping Gemini 5 overcome fuel cell problems to that nearly curtailed its mission, and then with the dramatic rendezvous in space involving Geminis 6 and 7. When Kraft moved to preparations for Apollo in 1966, Hodge became lead flight director for Gemini 8, and after that flight, he too moved on to Apollo.

When Gemini wound up at the end of 1966, Hodge was given a NASA Exceptional Service Medal for “planning and directing the flight control aspects of manned space flight missions and in developing highly proficient flight control teams necessary for the conduct of the missions.” Shortly before that, Hodge flew to his ancestral home to receive an honorary doctor of sciences degree from the University of London.

Kraft, Hodge and Kranz were set to return to their original rotation for the first crewed Apollo flight in February 1967, and Kraft and Hodge were on console in Houston on January 27 when a fire consumed the pure oxygen atmosphere inside the spacecraft, killing astronauts Virgil I. Grissom, Edward H. White and Roger Chaffee.

Hodge was involved in the work of investigating the fire’s causes and making needed changes to the spacecraft. On January 22, 1968, Hodge worked his final shift as a flight director during the robotic flight of the first lunar module in Apollo 5.

While both Kraft and Kranz rated Hodge highly for his intellect and ability as a planner, and Hodge’s actions in Gemini 8 won universal praise, his two colleagues said he was not known as an effective manager. Kranz described Hodge in his memoirs as someone who sought more consensus and was more philosophical and thoughtful than his peers.

Hodge had become a U.S. citizen in November 1964, and he and his wife had two sons and two daughters, who all survive him. In 1961, he and other British engineers who worked for the space agency formed a NASA cricket team that played a game against William and Mary University in Virginia.

From July 1968 to his departure from NASA in June 1970, Hodge was manager of Advanced Mission Programs at the Manned Spacecraft Center. By then, he was already working on the Apollo missions that would follow the first lunar landing. “I was beginning to worry that no one was looking at the second lunar landing. The whole organization was concentrating on the first, and it seemed to me that if you have 10 or 12 sets of hardware, you have to start worrying about the rest of the program,” he said.

By February 1969, Hodge’s group had written specifications for a Lunar Module that could stay longer on the Moon, carry more equipment such as a lunar roving vehicle down to the Moon, and bring more lunar samples home. That spring, his group also drew up changes to be made to Apollo's Service Module to allow the placement of scientific instruments to photograph and measure the Moon. Hodge’s office was also charged with looking beyond Apollo to programs such as a permanent space station, a reusable spacecraft, and trips to Mars.

After leaving NASA in June 1970, he spent most of the next 12 years working on advanced transportation concepts in various positions at the Department of Transportation, first in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and later in Washington, D.C. From 1974 to 1976, he did similar work for the Urban Transportation Development Corporation in Toronto, Ontario, a corporation owned by the Government of Ontario that is remembered for developing elevated transit systems in Scarborough, Ontario, Greater Vancouver B.C., and Detroit.

“I had the job of sort of looking to the future,” Hodge said of his work for the Department of Transportation. “What directions technically and politically and all that kind of thing could we take the department to be useful in the field of transportation? It was a tremendously broad subject and I had a wonderful time. We did a lot of studies on the future of the air traffic control system. We did a lot of stuff on high-speed railroads, looking at passenger situations, and came to the conclusion that there was nowhere in the United States where railroad passenger traffic made any sense at all. It would never be profitable.”

While he worked on advanced planning at NASA, he befriended another engineer named James Beggs, and they met again working at the Department of Transportation. When Ronald Reagan became president of the United States in 1981, he selected Beggs to be Administrator of NASA, and Beggs’ call for NASA to develop a permanent space station got Hodge’s attention.

In May 1982, Beggs announced the formation of a space station task force headed by Hodge, who controversially refused to consider designs advanced by the Johnson Space Center and the Marshall Space Flight Centers, and refused to even suggest what the station might look like in order to protect the station from critics who would look for deficiencies. The Task Force instead focused on canvassing potential users for a space station on what they would want out of a station, and also put out study contracts to major aerospace companies for station concepts.

The U.S. military wanted nothing to do with the station, and others in the administration opposed it because of the cost, but Beggs, his deputy Hans Mark and Hodge and his team eventually won over the president, who announced his support for a space station in his 1984 State of the Union Address, followed by Congress.

In April 1984, Beggs announced the formation of an interim office of space station at NASA headquarters, headed by Phil Culbertson, with Hodge as his deputy. The office was made permanent on August 1, and Hodge became deputy associate administrator for space station.

The space station team also began work on defining what the station would look like and, more importantly, who in NASA would do what. Hodge envisioned a station operating in a standard equatorial orbit from Cape Canaveral supported by two robot platforms where experimental work could go on without concern for human contamination. Hodge stressed “operational autonomy” in his design concepts for a station that could operate independent of ground control. The former flight director realized that the cost of maintaining the ground control infrastructure would drive the station’s costs to a prohibitive level.

NASA began to undergo a series of changes triggered in part by the departure of Beggs as administrator in late 1985. Soon NASA was reeling from the impact of the Challenger disaster, and later in 1986, Hodge was given a reduced role as infighting grew between NASA centers for their shares of station work. Hodge explained: “I made the bureaucratic mistake of trying too many things at the same time. New ideas in management, technical management. By this time, NASA had become stodgy, very bureaucratic.”

He left NASA for the last time in 1987 and became a consultant based at his home in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., where he said he enjoyed “picking and choosing who I’ll work for.” At the time of Apollo 11, NASA had given Hodge another NASA Exceptional Service Medal, and he won a NASA Outstanding Leadership Medal in 1985 for his work on the space station.

Hodge’s passing came two months after that of fellow flight director Glynn Lunney and nearly two years after the death of Chris Kraft, leaving Gene Kranz as the only surviving member of the original generation of NASA’s flight directors. The space station he helped bring to reality underwent many design and management changes after Hodge left NASA, becoming the International Space Station prior to its long-delayed start of construction on orbit in 1998.